![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

...

...

.....

...

...

...

...

CERN

Flusser

Lord's Bridge

Lightning Field

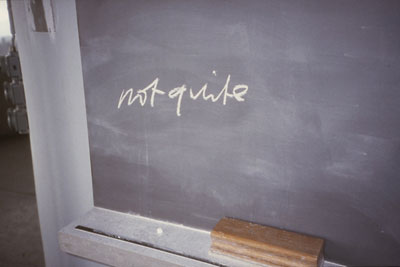

CERN, blackboard at the top of the water tower, 2000

[Photograph | Tim O'Riley]

(Text

from exhibition catalogue)

It's difficult to know where to begin. I visited CERN on three separate occasions and was free to find my own way around, to talk to whoever might be willing to stop and chat. A lack of knowledge of the real language - mathematics - spoken by most at CERN put me in the position of outsider as far as the specifics of the research were concerned. The challenge seemed to be to find my own foothold, a space in which to operate amidst the vastness of the enterprise - the place, the experiments and the ideas.

Given that the particle beams in the big accelerator are travelling at close to the speed of light and make a complete circuit (27 km) about 11,000 times per second, you start to get an idea of the relative scales involved by walking along the main accelerator tunnel. This is situated deep underground and curves endlessly out of sight in both directions. Occasionally, in the labyrinthine spaces where the main detectors are installed, you would come across modest signs of life (an old table and chair in a seemingly forgotten corner, for example), evidence of a human presence within the machine.

Above ground, many of the compound buildings seem anonymous and have

an air of impenetrability, whilst the roads that criss-cross the site

bear the names of illustrious predecessors (Planck, Einstein, Schrodinger,

for example) reminding you that those at CERN routinely use these names

- and all that they represent - to navigate. Routes Bloch and Gregory,

in particular, became well travelled roads for me, leading, as they do,

from the visitors' hostel, along the perimeter fence, to the chateau

d'eau. Situated high above the ground, the water tower's circular observation

room became a good place to cogitate whilst looking out over the main

compound and the surrounding terrain, with mountain ranges - the Jura

and the Alps - bordering it on two sides.

Inside the experimental spaces, there is a different sense of the outside

world and the scale which defines it. Here, attention is focused inwards,

towards a horizon at which everything whatsoever is more than gaseous,

a swarm of energy or 'quantum foam' as John Wheeler put it. It seems

easy enough to say that matter and energy at this level are interchangeable

but more difficult to comprehend when you look at something apparently

solid and reassuring like a table, a brick or, for that matter, a mountain

range disappearing off into the distance.

Trying to fathom ideas like these, I often found myself looking up at

the expanse of sky above CERN. The sky was frequently streaked with the

vapour trails left by long haul jets, making me wonder about the behaviour

and whereabouts of all those particles speeding around the accelerator

far beneath my feet. Back in London, I continued to watch the sky and

noticed on one occasion, that the heat from a jet's engines had burnt

a kind of negative vapour trail through the high altitude clouds, as

if someone had cut them with a blunt knife. It seemed strangely relevant

and I spent much time waiting with my camera for it to happen again.

Ernst Mach, (after whom the Mach numbers in supersonic flight are named),

said: 'Time is an abstraction at which we arrive by means of the changes

of things'.* I remember putting this to the test whilst waiting for a

train in Geneva station, looking at the clock and trying to see the minute

hand move. It dawned on me that patience and probability are embedded

within the work that happens at CERN. This, together with a sense of

the apparent strangeness at the heart of things, continues to puzzle

me. That and the fact that physicists don't always agree on how to interpret

what they see or what they think they see.

(* Ernst Mach, The Science of Mechanics, 1883; quoted in Julian Barbour, The End of Time, Weidenfeld & Nicholson 1999, p67.)

![]()

![]()

![]()